Title: Mirandas Atemwende

Instrumentation: Chamber opera with mezzo-soprano and two speakers

Year: 2014–15

Duration: approx. 40 min.

Premiere: Kontraklang Festival 2015

Performers: Kammerensemble Neue Musik Berlin

Mirandas Atemwende is the second act to my opera Die Geisterinsel that was premiered at the Staatsoper Stuttgart in 2011. Die Geisterinsel is based upon a late 18th century Singspiel with the same title by the German composer Johann Rudolf Zumsteeg, a contemporary of Mozart, and is an adaption of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. The music is in the late-Classical style of Mozart and Haydn and the libretto by Wilhelm Friedrich Gotter is characterized by its classically elevated German reminiscent of Goethe, which stands in sharp contrast to Shakespeare’s “late style” writing with its condensed information, vernacular style and somewhat harsh and jagged rhythms.

In Die Geisterinsel, this late-Classical musical style of Zumsteeg, its formal structures, harmonic language, etc., are reworked within my own noise-based aesthetics. After its premiere, I later felt the need of a second act in order to somehow balance and enrich the main characters of Die Geisterinsel, where Caliban and Miranda and their respective relationship to Prospero introduce a more subtle critique of Prospero’s dominant position on the island where Shakespeare’s Tempest takes place.

Influenced by the Cambridge (U.K.) poet J. H. Prynne’s analysis of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 94 (“They that Haue Powre to Hurt”) where he exhaustively excavates its highly condensed semantic structures, as well as Paul Celan’s energetic and sound-focused translations of the Shakespeare sonnets, I began to work with texts as material more than as a carrier of narrative meaning and ideas.

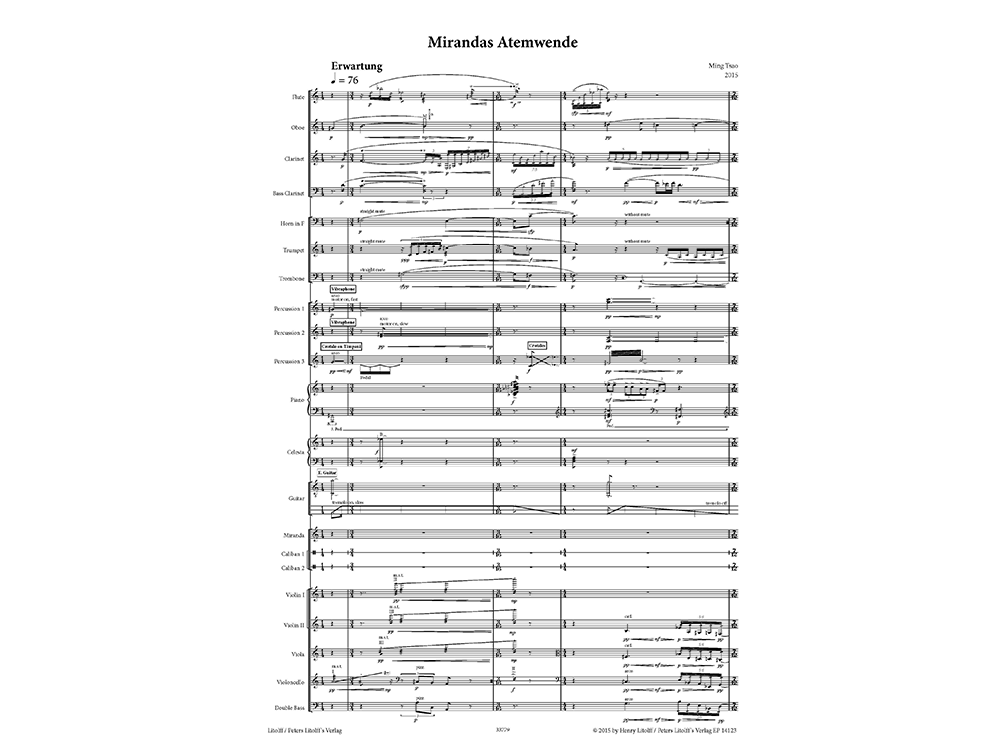

Mirandas Atemwende is structured in twelve tableaus, of which three are instrumental and nine sung or spoken by either Miranda or Caliban.

Mirandas Atemwende (Miranda’s Breathturn)

1. Erwartung (Expectation)

2. Es gibt einen Ort (There is a Place)

3. Du entscheidest dich (You Make a Choice)

4. Heute (Today)

5. Helligkeitshunger (Brightnesshunger)

6. Das Geschriebene (The Written)

7. Fadensonnen (Threadsuns)

8. Stehen (To Stand)

9. –vor der Erstarrung (Before Paralysis)

10. Caliban’s Wound Response

11. Against Hurt

12. The Wound Day and Night

In Mirandas Atemwende, only Miranda and Caliban remain as characters from Die Geisterinsel who extend their resentment of Prospero’s authority over them to a more general critique of Prospero’s language and its implied relations of hierarchy and power. The first eight tableaus of Mirandas Atemwende focus on Miranda through a radical reworking of Arnold Schönberg’s monodrama Erwartung. A sense of expectation (Erwartung) for the possibilities of a radically new language, musical and poetic, away from Prospero’s influence (and in Schönberg’s case, from tonality) condition these tableaus. By quoting expressionist musical gestures rather than building upon a psychologically rooted expressionism, the music could be regarded as a “documentary about expressionism,” where expression is mediated through the lyric in music subjected to a stringent formal rigor accompanied by the often delicate balance between extreme organization and unfocussed chaos.

The libretto begins with syllabic fragments from Paul Celan’s translation of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 105 and concludes with poems taken from his collection Atemwende, where the very integrity of the German language is put into question. Celan’s translation of Shakespeare into German, with its particular emphasis on sound and the materiality of language, is a stepping stone into his own poetry in which poetic expression is clearly alienated, broken and bordering upon mute. Celan’s poetry as Miranda’s text, whose words are forged together (zusammenschmieden) from fundamentally different categories (such as “Wortmond” or “Wundenspiegel”), creates a metaphorical language that escapes Prospero’s garden of rational discourse and reestablishes a necessary relationship between fact and value in order to have a power of consequences, a sense of existential meaning and purpose that had been lost on the island.

Miranda’s “Atemwende”symbolizes a radical poetic reorientation and solstice of breath by means of which poetry (Miranda’s newly discovered language) is actualized. As Celan states in his Meridian speech: “The attention the poem tries to pay to everything it encounters, its sharper sense of detail, outline, structure, color, but also of the ‘tremors’ and ‘hints,’ all this is not, I believe, the achievement of an eye competing with (or emulating) ever more perfect instruments, but is rather a concentration that remains mindful of all our dates.” Miranda’s final lines from Gotter’s libretto of Die Geisterinsel, “Ich will alle meine Sinne anstrengen” (I want to exert all of my senses), mirror Celan’s sentiments, to become more “mindful of all our dates” (which the Geisterchor, as spirits of the island, remind her of in Die Geisterinsel), that is, to have a greater awareness of one’s sense of being which Prospero’s more “perfect instruments” have reduced to an abstraction of numbers. Miranda recites Celan’s text “in order to speak, to orient myself, to find out where I was, where I was going, to my reality.” As Celan notes: “A poem… may be a letter in a bottle thrown out to sea with the—not always strong—hope that it may somehow wash up somewhere, perhaps on a shoreline of the heart. In this way, too, poems are en route: they are headed toward. Toward what? Toward something open, inhabitable, an approachable you, perhaps, an approachable reality.”

Miranda’s poetic language becomes the place for such an encounter—a meeting that conquers the self-distance she has acquired through Prospero’s education and her isolation on the island—from which she can construct an identity for herself. Miranda’s message in a bottle cast away from Prospero’s island is, throughout the opera, underway and her voice comes to symbolize fragility through this possibility of an unanswered poetic invocation. Miranda, through Celan’s poems, seeks communication, contact, connection outside of the island: “there are / still songs to sing beyond / mankind.” Celan’s poems almost always have a “you” (dich) to whom the poems are addressed. “The poem wants to head toward some other, it needs this other, it needs a counterpart. Everything, each human being is, for the poem heading toward this other.” Miranda reaches for this other in the absence of Prospero who is now gone, a counterpart to which she can be underway and headed toward. Indeed, Miranda embodies poetic discourse from the very beginning —the desire to forge Prospero’s words into a new language that cannot divide and classify, one that explores the very limits of consciousness and establishes a necessary relationship to truth. In this sense, Miranda becomes fully aware of her potential—as poetic discourse—for propelling and allowing action. Through Miranda, poetry and music become the necessary force to counter Prospero’s art by offering an alternative that is not dominated by instrumental reason and accepts the island as it is (and not to be cultivated into a garden), revealing a history far older than when Prospero arrived whose stewardship Miranda now feels responsible for.

The last third of Mirandas Atemwende tableaus nine through twelve, focus on Caliban. Tableaus nine and ten, in particular, reference a part from Mouvement (–vor der Erstarrung) by Helmut Lachenmann. Lachenmann’s idea by the time of composing in the early 1980’s was to take the material of “noise” and to bring it into a compositional sound structure. Taking this as a metaphor for Caliban’s awareness of Prospero’s taming or colonizing of the island through his art (or compositional “language”) and with poems from The White Stones and Word Order by J. H. Prynne, Caliban’s consciousness is enriched so that he may “dissolve the bars to it and let run the hopes, that preserve the holy fruit on the tree”, that is, for Caliban to become more acutely aware of the material processes of the island from which Prospero’s language had alienated him. In these tableaus, Caliban attempts to address the wound inflicted by Prospero’s language, the wound that remains gaping through Celan’s poetry. Caliban uses Prynne’s poetry to express “the paradigmatic moment of impulsive feeling which escapes, or rather precedes, the conscious attempt to process and understand it,” an impulsive feeling that is then diagnosed in Mirandas Atemwende as “the moment of pain.” One can also hear faint echoes of Lachenmann’s “…zwei Gefühle…” when the wound is opened up by Caliban’s “two feelings” (represented by two separate actors) for the “threatening darkness” of Prospero’ garden and his own “desire to see with my own eyes” whatever wonderful things might be on the island in Prospero’s absence, “in order to behold the beautiful wilderness of the other side of being.”

Caliban, like Miranda, is wounded by Prospero’s enlightenment education and the desire to break up the continuum of time with ever more perfect instruments. Caliban’s response is to rediscover those natural processes of the island, “the unison of forms,” and to let them flow again. “If we arbitrarily break up the continuum of time into fixed intervals, upon which we then project hopes or expectations deferred from the present, we lose contact with natural processes.” Similar to Friedrich Hölderlin’s sentiments in his famous poem Hälfte des Lebens, “‘fruit’ should not be declared ‘holy’, with the sense of being set apart, usually preserved on a tree. The fruit is a stage in the continuing cycle of the plant’s life, not just the final outcome. Whatever lives by continuous change and development, we distort by solidifying—unless we are able to ‘let run’ what at present we anxiously ‘rein in’.” Caliban’s words come from a renewed, heightened attention to the processes of the island, a vantage point where the final nail is driven into the coffin of Prospero’s art.

The compression and intensification of verbal and musical language in Mirandas Atemwende are ways of engaging with a late modernist form of expression that makes the connections between romanticism and formal rigor, extreme expressionistic abstraction and documentary “authenticity.” In working with expressionism as a way to let the material express itself but without psychologizing is to renew the idea of the lyric in contemporary music that becomes in my music fractured, damaged, multi-perspective, complex and problematized in order to negotiate the complexities of the surrounding world. Lyrical subjectivity is ultimately placed in the musical sounds themselves rather than with a single consistent “speaker”, a sense of artistic expression that embraces the exteriority of the world rather than retreating from it, an orientation to which filmmaker Danièle Huillet catches the essence of in a few words: “It’s just the world. And who owns that?”

Link: www.wisemusicclassical.com/work/74716/Mirandas-Atemwende–Ming-Tsao/